India’s high rice yields come at a nutrient cost. What about Bangladesh?

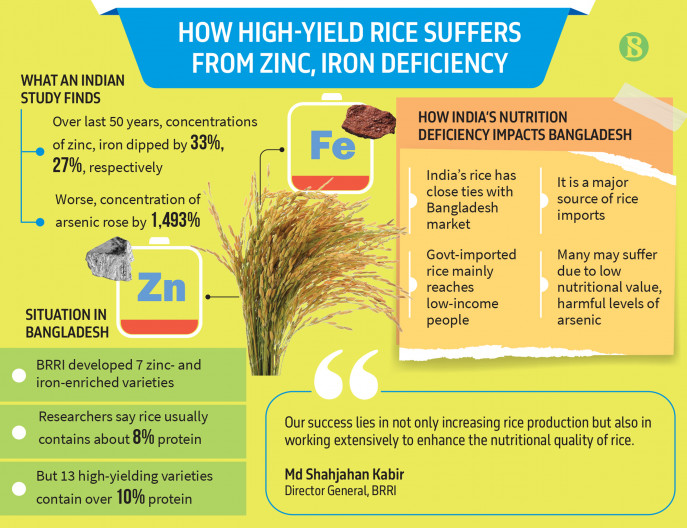

While India has relentlessly developed and increased the use of high-yielding rice varieties over the past 50 years, similar to Bangladesh, to build a strong foundation for food security, a study reveals this success has come at a cost: a worrying decline in essential nutrients such as zinc and iron in these grains.

Although India has conducted a study, there has been no such move in Bangladesh, said the heads of two major research institutes involved in the development of high-yielding rice varieties.

However, referring to recommendations by Indian researchers to increase nutrients to bring them to normal levels, researchers in Bangladesh said they have discovered varieties with higher than normal nutritional content in rice over several years.

Indian magazine Down To Earth recently published a report on how high-yielding varieties are becoming nutritionally deficient, citing a study by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR).

Apart from revealing information on declining nutrition, the study also found that the levels of arsenic, which is harmful to health, increased significantly.

ICAR researchers say modern varieties are less efficient at sequestering nutrients like zinc and iron, despite their availability in the soil. Consequently, over the past 50 years, concentrations of essential nutrients such as zinc and iron have decreased by 33% and 27% in rice and 30% and 19% in wheat, respectively.

Worse, the concentration of arsenic, a toxic element, in rice increased by 1,493%. That is, the staple food grains rice and wheat are not only less nutritious but also harmful to health. In the constant genetic tampering under modern breeding programmes, breeds have also lost their defence mechanisms against toxic substances.

Researchers in Bangladesh are developing new varieties through modern genetic tampering.

The Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI) has developed seven zinc- and iron-enriched varieties. Additionally, there are 13 varieties that have added protein.

However, there is debate regarding the extent to which these varieties are being cultivated in the field and whether they are specifically available on the market.

According to BRRI researchers, rice usually contains about 8% protein. However, there are 13 high-yielding varieties that contain more than 10% protein. Additionally, seven new varieties have been developed that are universally zinc and iron enriched.

BRRI Director General Md Shahjahan Kabir told TBS, “About 13% of the rice produced in the country is enriched with zinc and iron. On the other hand, varieties are being developed with increased protein levels.”

He added, “Our success lies in not only increasing rice production but also in working extensively to enhance the nutritional quality of rice.”

India’s rice and wheat have a close relationship with the Bangladesh market. India serves as a major source of imports for rice and wheat, both publicly and privately. However, it’s worth noting that India has currently halted the export of rice and wheat.

Although private sources make rice and wheat available in the market through various channels, rice imported through government departments reaches low-income individuals at a subsidised price.

It creates fear that the people of Bangladesh may also suffer due to rice contaminated with low nutritional value and harmful levels of arsenic.

Down To Earth magazine reports a “historical shift” in the nutrient profiles of rice and wheat, warning that the impoverished staple grains could exacerbate the country’s growing burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

When the Green Revolution began in India, the goal was to feed a rapidly growing population and become self-sufficient in food production, researchers say.

Hence, after the 1980s, breeders’ focus shifted to breed innovation. Varieties that are developed are pest and disease resistant and tolerant to conditions such as salinity, humidity, and drought.

They didn’t have time to think about whether the plants were getting nutrients from the soil or not. Hence, over time, plants lose their ability to absorb nutrients from the soil.

In Bangladesh, a similar situation unfolded. In the same context as India, aiming to ensure security in rice production, the main food grain of the people, the green revolution began in Bangladesh in 1973.

In this country, too, researchers are focusing on high-yielding varieties to feed the rapidly growing population. Thanks to the development of high-yielding and resistant varieties, the country is now self-sufficient in rice.

Production of 3.90 crore tonnes of rice was possible in the fiscal 2022-23, whereas the country’s rice production was only in the range of 1 crore tonnes immediately after independence.

The Agricultural Extension Department emphasises that achieving self-sufficiency in rice is only possible with the help of high-yielding varieties. Good rice production is attained through the development and extension of these varieties.

According to the agriculture ministry, Ufshi seeds were predominantly utilised during the Aus, Aman, and Boro seasons. In the fiscal 2019-20, farmers across the country used a total of 142,283 tonnes of Ufshi seeds and 15,777 tonnes of hybrid seeds, with only 260 tonnes of local paddy seeds being utilised.

Two institutes in Bangladesh – BRRI and the Bangladesh Institute of Nuclear Agriculture (BINA) – are dedicated to developing high-yielding rice varieties. Together, they have developed a total of 137 varieties, including two high-yielding hybrid varieties. Most of these varieties are high-yielding, contributing to the country’s rice production.

Researchers say there is no detailed study on whether the nutritional value of high-yielding varieties is decreasing. However, there are many studies on soil properties, including excessive fertilisation, soil erosion, and loss of nutrients due to repeated cropping of the same land.

In this context, researchers admit that the possibility of reduced nutritional value in plants and rice is by no means insignificant.

BINA Director General Mirza Mofazzal Islam told TBS, “Although we don’t have research on genetic potential, we are already doing some work. We have developed rice varieties enriched with zinc and iron, which are being cultivated in the field as well.”

He continued, “We are developing varieties with these nutrients through biofortification. In other words, even if there is a deficiency in the soil, we have created an opportunity to address it through this special variety.”

This article has been republished from The Business Standard.