Rice prices drop brings relief to billions worldwide, risk for farmers

By Pratik Parija, Anuradha Raghu and Katarina Höije

From the Philippines to Senegal, billions of people are finding it easier to feed their families now that rice prices have plunged off 15-year highs.

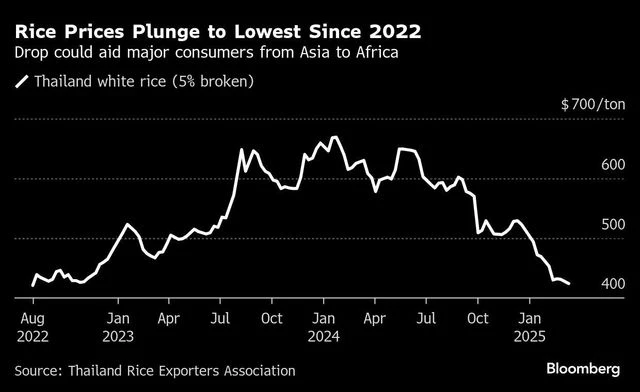

Favourable weather over the past year has helped lift global stockpiles for a second season, and a further flood of the crop is expected from top shipper India, which has scrapped long-running export restrictions. The abundance has pushed the price of Thai white rice — an Asian benchmark — to the lowest since 2022 and more than 30 per cent below last year’s peak.

While it takes time for changes on the wholesale level to feed through to shoppers, the price drop is already bringing relief to households struggling with otherwise high living costs.

“I don’t have to worry all the time about how to feed my children,” said Yassine Toure, whose dozen family members in Dakar consume 25 kilograms (55 pounds) of rice a week. The staple grain for more than half the global population had been so expensive that, at one point, buying it was seen as a luxury, she said.

“Now we can finally breathe a bit easier,” said the 32-year-old who works as a cook at a roadside eatery in the Senegalese capital.

The cost of rice had begun climbing a few years ago as a hot and dry El Niħo weather phenomenon hurt production of the water-dependent crop. That spurred India to announce export bans in an effort to shore up supplies, further compounding the shortfall.

)

Good rainfall last year helped boost output in Asia and forecasts that El Niħo won’t develop during India’s June-September rainy season in 2025 has spurred expectations that international prices will keep declining. Moreover, the South Asian nation’s recent rollback of its export restrictions to prevent a glut at home will serve to further pad global supplies.

“As the world’s largest rice exporter, India is keen to regain the markets that it had to give up during the export controls,” said Peter Timmer, Professor Emeritus at Harvard University, who has studied food security for decades.

The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization this month increased its 2024-25 global rice output estimate by 3.6 million tonnes to 543 million tonnes, mainly reflecting buoyant crop prospects in second-biggest grower India. Higher-than-previously-anticipated plantings of off-season crops have also boosted the production outlook for Cambodia and Myanmar, it said. That will boost ending stockpiles to 206 million tonnes, up from roughly 200 million tonnes in 2023-24.

While good news for consumers, ample stockpiles and falling prices are creating challenges for farmers and their profit margins. If prices fall too far, it could spur farmers to plant less in the approaching season, risking a cut in supplies, according to Shirley Mustafa, an economist at the FAO.

Thai growers last month protested the low prices and called for the government to boost support after a $56 million subsidy plan failed to meet their demands. In January, Indonesia’s food procurement agency stepped up otherwise routine buying from local farmers at a guaranteed price. It’s one of several rice-producing countries, including India, that has mechanisms to protect growers from price fluctuations.

“Low prices are bad for any producing country like India because they have reduced the profit margins of exporters as well as farmers,” said B.V. Krishna Rao, president of The Rice Exporters Association.

Thai farmer, Sutharat Kaysorn, can attest to that pain. Already unable to repay her loans on time, she says she is unlikely to be able to take out any more credit for the next harvest.

“The current paddy prices are not even enough to cover production costs such as fertilizers and workers’ wages,” said Kaysorn, who has about 100 acres of rice fields in Sing Buri province north of the Thai capital, Bangkok.

Retail prices in various countries are determined by factors like the level of reserves in importing nations, the strength of the local currency, transport expenses and the cost of credit to finance overseas purchases, the FAO’s Mustafa said.

In nations like the Philippines, rice accounts for a significant chunk of the consumer price basket, making it a focus of policymakers due to its impact on broader inflation. The government was forced to intervene last month to bring down persistently high prices by declaring a food security emergency and releasing rice buffer stocks. That’s now helped ease local prices and free up disposable income for residents like Fheri Oris, 49, and her family of three.

“The savings are not substantial but help relieve the pressure on our household budget,” said Oris, who also sells rice in her mom-and-pop store in Batangas province. “When prices fall, people tend to buy more. I hope it stays that way.”

This article has been republished from The Business Standard.